Introduction to Kito Aya and Her Diary:

木藤亜也(Aya Kito)(July 1962 - May 23, 1988) went into eternal sleep at the age of 26, surrounded by flowers as she wished and left on her journey. Her diary, namely 1リットルの涙(1 litre of tears) was then published after her death and series was too filmed based on her real life story which is recorded in her diaries.

Aya Kito was diagnosed with a disease called Spinocerebellar ataxia when she was 15 years old. The disease causes the person to lose control over their body, but because the person can retain all mental ability the disease acts as a prison. Aya discovers this disastrous news as the disease has already developed. There is no cure. Through family, medical examinations and rehabilitations, and finally succumbing to the disease, Aya must cope with the disease and live on with life until her death at the age of 26.

Chapter 1 14 Years Old (1976-77) - My Family

Mary Died

Today is my birthday. How big I've grown! I think I should thank Mom and Dad. I'm determined to get better grades and be much more healthier so that I won't disappoint them. That's part of the reason why I want to enjoy the prime of my life. I don't want to have anything to regret in the future. I'm going to a school camp the day after tomorrow. I must study hard to finish my homework, otherwise I won't feel free. Keep it up, Aya!Tiger, the neighbors' fierce dog, bit Mary on the neck, and she died. Tiger is big, but Mary was very small. She went up to him wagging her short tail to show she was friendly.

"Mary, no! COME BACK!" I shouted desperately, but . . . She died without being able to cry out. That must have been so frustrating for her. If she hadn't been born a dog, she wouldn't have had to die so soon. Mary, I hope you'll be happy wherever you are!

Our new house is finished. The bug room on the east side of the second floor is like a castle for me and my younger sister, Ako. It has a white ceiling and the walls are brown veneer. The scenery through the windows is different from what I'm used to. I'm happy we have our own room, but a big room makes me feel a bit lonely. I wonder if I'll be able to sleep tonight?

Starting in a fresh mood!

1. I should wear T-shirts and pants (more comfortable for moving around in).

2. Daily tasks:

*Watering the garden

*Weeding

*Checking if there are any insects on the backs of the leaves of the tomato plant I planted

*Checking for lice on the leaves of the chrysanthemums and getting rid of any I find at once

3. I mustn't neglect my studies!

4. Besides all these, I should record what happens everyday in my diary . . . without fail.

I order myself to do all these things.

Dad: 41 years old. He's a bit impetuous, but sweet.

Mom: 40 years old. I respect her, but she's tough when she goes right to the heart of the matter.

Me: 14 years old. At the start of adolescence. A delicate age. A crybaby, in short. Emotion incarnate. Simple girl. Loses temper easily, but also laughs easily.

Ako: 13 years old. I have a sense of rivalry with her in terms of both study and personality. But these days she has me under pressure.

Hiroki: 12 years old. A tough customer. Formidable. He's younger than me, but he sometimes seems more like an elder brother. He's also Koro the dog's foster father.

Kentaro: 11 years old. He has a rich imagination but can be careless.

Rika: 2 months old. She has Mom's curly hair and Dad's face (her eyes in particular, the hands of the clock pointing to eight twenty). Very cute!

Chapter 2 15 years Old (1977-78) - Illness Creeping Up

Signs of Something

Recently, I seem to be getting skinnier. I wonder if it's because I've been skipping meals to do all my homework and independent research? Even when I think of doing something I can't carry it out, and that gets me into trouble. I blame myself, but I can't make any progress. I'm just wasting energy. I want to put on a bit of weight. I'll try to take action starting tomorrow so that my plans won't be ruined.

It was drizzling. "I hate going to school holding an umbrella as well as carrying my heavy schoolbag and another bag." Just as I was thinking this, my knees suddenly seemed to collapse and I fell over on a narrow graveled road. I was only about 100 metres away from home.I banged my chin hard. I touched it gently and found my fingers were covered with blood. I picked up my bags and umbrella that were scattered on the road and retraced my steps back home.

"Have you forgotten something?" Mom called as she came out into the entrance hall. "You'd better hurry up or you'll be late! . . . Oh dear, what happened?"

All I did was cry. I couldn't say anything. Mom quickly wiped my blood face with a towel. There was some grit in the cut.

"I think this is a job for the doctor," said Mom. She quickly helped change out my wet clothes and firmly applied a plaster to the cut. Then we jumped into the car.

I had two stitches without any anesthesia. It was all a result of my clumsiness, so I tried to bear the pain with my teeth clenched. But, more important, I'm sorry, Mom-because of me you had to take a day off work.

Looking at my painful chin in the mirror, I wondered why I didn't put my arms forward to break my fall. Was it because my athletic ability is poor? I was pleased, however, that the cut was at the back of my chin. (If I had a scar in some more visible place, that future would be a closed book for me in terms of marriage.)

My physical education scores so far:

First grade at junior high-3

Second grade-2

Third grade-1

How disappointing! Lack of effort? I was hoping to gain a bit more strength with the circuit training during the summer holiday. But I failed. I didn't do it long enough. So I suppose it's not surprising. (Of course it isn't! = The mystery voice of my other self.)

This morning, the sunlight and a pleasant breeze were coming in through the yellow lace curtains on the kitchen window. I was crying.

"I wonder why it's only me that's so poor in athletic ability?"

In fact, we had a balance beam test today.

"But you're good at other subjects, so it's all right, isn't it?" Mom said, looking down. "In the future, you can make the most of your ability in your favorite subject. You're very good at English. So why don't you try and thoroughly master that? It's the international language, so I'm sure it'll be useful in the future. It doesn't matter if your score for PE is only 1 . . ."

I stopped crying. Mom made me realize that I still have some hope.

I'm becoming more and more weepy. And my body won't move the way I want it to. Am I getting a fluster because I'm lazy about doing my homework, which I could only finish if I spent five hours a day on it? No. Something inside my body seems to be going wrong.

I'm scared!

I have a feeling that tightens my heart.

I want to get more exercise.

I want to run with all my might.

I want to study.

I want to write neatly.

I think Paul Mauriat's Toccata is really nice. I've grown very fond of it. When I play it while I'm eating meals, the food tastes so good, it's like a dream.

Now, about Ako, one of my sisters. Up to now, I've only noticed the ill-natured of her character. But now I can see that she's actually very kind. Why do I think that? Well, I'm very slow when we walk to school in the morning, but she always stays with me. My brothers just walk on ahead and leave me behind. But when we were crossing a pedestrian bridge, Ako took my schoolbag off me and said, "Aya you'd better hold the handrail while you go up."

I'm pretty well out of the summer holiday mood now.

As I was going upstairs after clearing up the dinner things, Mom said, "Aya, can you come and sit down for a moment?" She looked very serious. I became tense, wondering what she was going to tell me off about.

"Aya," she said, "you seem to be walking with your upper body leaning forward and you're rolling to the right and left. Have you noticed that yourself? I've noticed you've been doing that for a while, and it's beginning to worry me. Shall we go to the hospital for a checkup?"

". . . Which hospital?" I asked after a pause.

"I'll find one that can give you a thorough examination. Leave it up to me. All right?"

My tears flowed nonstop. I really wanted to say, "Thank you, Mom. I'm sorry for causing you such anxiety." But I was stuck for words.

Since Mom has suggested I should go to a hospital, I've been wondering if there really is something wrong with me.

Is it because my athletic ability is so poor?

Is it because I stay up late?

Is it because I eat irregularly?

I couldn't help crying as I was asking myself those questions. I cried so much, my eyes hurt.

Chapter 2 15 years Old (1977-78) - Illness Creeping Up II

Seeing The Doctor

I go to the hospital in Nagoya with my mother. (Written by Aya in English).We left at 9 a.m. Rika, my baby sister, wasn't feeling well, but she had to go to her nursery school anyway because I was going to the hospital . . . poor girl!

We arrived at Nagoya University Hospital at 11 a.m. We had to wait for about three hours. I tried to read a book, but I was feeling nervous. I couldn't concentrate as much as usual because I was feeling rather worried.

"I rang Professor Itsuro Sofue (now Director of Chubu National Hospital)," Mom said, "I'm sure you'll be all right."

But . . .

At last my name was called out. My heart was beating fast. Mom explained my problems to the doctor:

1. I fell over and cut my chin. (A normal person would put out their arms to break the fall, but my face hit the ground directly.)

2. The way I walk is unstable. (I can't bend my knees much.)

3. I've been losing weight

4. My movements are slow. (I've lost the ability to move quickly.)

Listening to her, I was amazed. Mom is always moving around so busily, but now I know that she's been observing me very carefully! She knew everything about me . . . That made me feel more secure. So, the things I've secretly been worried about have been conveyed to a doctor. My worries will be solved.

I sat on a round chair and looked at the doctor. He was wearing glasses. He had a gentle look and a warm smile, so I felt relieved. He asked me to close my eyes, stretch out both my hands and try to make my forefingers meet. Then I had to stand on one leg. Then I lay down on a bed and he stretched and bent my legs. He patted my knees with a hammer. I was totally under his thumb. Then the examination was over.

"Now let's take a CT scan," he said.

"Aya," said Mom, "it won't hurt you or anything. It's only a machine tat checks ur brain by cutting it in round slices."

"What! Cutting my brain in round slices?"

That's a very serious matter to the person being scanned! A big machine slowly came down from above. My head was completely covered. It was as if I was riding in space. A man in a white frock said, "Lie down still and don't move." I lay still just as I was told. Then I began to feel sleepy.

After the examination, we were kept waiting for a long time. Then we got some medicine and went home.

I have added one more order to my list:

I won't complain about taking medicine-even if it's enough to fill up my stomach-so long as it makes me better. Dr. Sofue at the prestigious Nagoya University Hospital, I beg you, please help to save the life of Aya, the budding beauty. You told me that I should only go and see you once a month because the hospital's far away and I have to go to school. Well, I'll definitely come and see you, and I will do whatever you tell me to do. So please make me better, I beg you!

Chapter 3 16 Years Old (1978-79) - The Start of Distress

The wheelchair

"Aya," said Mom, "we're going to buy you a vehicle!"

"What!?"

She started explaining slowly. "The corridor has a handrail, but it may be dangerous when you want to go across. From a stand position, you'll have to sit down, crawl across, and then stand up again. This may cause you some anxiety when you're in hurry. And you often all over when you're changing your position. You won't be able to go outside, either, even if you want to. But it would be different if you had an electric wheelchair. You could easily operate it despite the weakness of your arms, and you won't have any problems even on slopes. It can move at speed of 5 kilometres per hour - the same as walking. So there's no danger, and it's very easy to operate. I think it would be perfect for you. But that doesn't mean you should get lazy, you know. It's not good to start relying on a wheel chair. You'll have to try to move using your own efforts as well. You mustn't neglect that. Have you been training properly?"

I was so pleased with the thought that i could freely go out. My world suddenly seemed to get wider. I've always wanted to act at my own direction. Up to now at a bookstore, I've had to show someone a memo with the title of a book written on it and ask them to go and find it for me. Fancy being able to pick up any book with my own hands! It's like a dream.

Great! I'll master the operation of the wheel chair and go out in it before I enter the school for handicapped.

Two men from a car maker delivered my wheelchair. I watched them assemble it. The wheels are moved by a motor. It has two batteries installed next to each other down below the seat.

"Aya, you have a ride. All you have to do is hold this bar and move it in the direction you want to go."

I tried sitting in the wheelchair. I pushed the bar forward slightly and the wheelchair slowly moved forward. It only makes a slight wound when it moves and turns. I practiced hard, but after a while, the tears started to flow-that's my nature, and I hate it!

"What's the matter?" Mom asked.

"I'm just so happy because I can move around again freely after such a long time!" I answered. But I couldn't express my complicated feelings very well.

I'm determined to practice until I can to get a bookstore. When I looked out through window, it was raining.

I worked very hard, including wiping the kitchen floor and cleaning the toilet. I wanted to vent my energy on something. My study is making a little progress. (I smile in glee, finding that I still have the spirit to study.) Rika calls my wheelchair 'The Chair' and my father calls it 'The Car'. And that's what it is in Japanese-kurumaisu-'a car-chair'!

I still remember something that happened when I was in the first grade of high school. Rika was about to play around with some wheelchairs lined up the corridor of the hospital. Mom said to her, "You shouldn't play around with wheelchairs. It's an insult to those who can only get around but riding in one/

I read about the prisoners in the German concentration camp of Auschwitz in the book Man's Search for Meaning. The book's a record of their experiences. Somehow, as a disabled person, I empathize with them. My experience seems to resemble theirs in terms of gradually becoming numbed.

Chapter 3 - The Start of Distress II

Friends of The Disabled

'Tanpopo no Kai' (The Dandelion Association) is a group of disabled people who got together somehow or other. They took me to a coffee shop calledBaroque which has a harpsichord. When I said, "I'd like to come here again when it's being played," Yamaguchi-san smiled.

I dropped by Jun's house. She's deaf, but she actively communicates through sign language. Her facial expressions are very cute. I've learned a little sign language. I want to become better at it and become a close friend. Jun's mother gives an impression very similar to Mom's.

What I've Learned from My Friends

1. If I remain timid, thinking I'm disabled, I'll never be able to change myself!

2. Rather than seeking after what you've lost, improve what you've been left with.

3. Don't think you're smart or you'll only feel miserable.

Chapter 3 - The Start of Distress III

Changing Schools, Life in A Dormitory

I arrived at the dormitory with a car full of household goods. The other students were also returning ready for the new term. The school has big rooms laid out like classrooms. Inside each one, there's an aisle running down the middle. It divides the room into left and right parts, on which there are tatami mats. Each student is provided with a cupboard and a fixed desk with a lamp. My new castle is the place nearest to the closet. Mom sorted out the things we'd taken to make my place comfortable.

"You won't need this yet," she said, "so I'll put it in the upper cabinet. But I'll put this near you because you often use it . . ."

The mothers of other students were also busily sorting things out. Nobody seemed interested in me. Whether that's good or bad . . .

"You should try and forget Higashi High School as soon as possible," Suzuki-sensei told me, "and become a student of Okayo (Aichi Prefectural Okazaki High School for the Physically Challenged.)"

So in order to 'forget as soon as possible', I removed my Higashi school badge and class badge and put the at the back of the drawer,

It's becoming really difficult now to move my legs forward. Holding desperately on to the handrail along the side of the corridor, I told myself "Don't be afraid, don't be afraid!" Tears came to my eyes as I thought, sadly, "I may perhaps . . . "

B-sensei's words flew over to me: "People are designed to be able to walk!"

I agree!

I empathize!

It's an unparalleled declaration of war!

"Climb Mt. Niitaka!" (the signal to start the attack on Pearl Harbor)

I fell over on the way to the classroom and started crying. A-sensei was just passing and assked me, "Are you sad?"

"I'm not sad," I replied, "just disappointed."

Why do people stand and walk on two legs? This is usually taken as a matter of course. The question came to me as I watched my friends walking briskly into the distance. Walking is really something . . .

I'm glad that I came here.

-Watching students playing baseball under the window . . .

-Watching students practicing sumo wrestling with the teachers . . .

But, getting accustomed to it is something else. I sometimes feel I'm in limbo. I've beun to accept the fact that I'm no longer a student of Higashi High. But I don't really feel that I'm a student of Okayo yet. If some stranger asked me, "Which school do you go to?", I wonder what I'd answer?

Chapter 3 - The Start of Distress IV

Emotional Turmoil

In the classroom, I said to A-sensei, "In my dream, when I stretched my back straight, I was able to walk briskly. You were pleased to see me doing that."

"Up to now," he said, "you've only had to think about your studies. But now you may be having a hard time with cleaning and other duties."

He then told me this:

"A child suffering from progressive muscular dystrophy wrote this poem:

God presented me with a handicap

Because He believed

I had the power to endure itIt somehow sounds like Hitler's words."

"Well," I replied, "I've actually had similar absurd thoughts, like 'I'm kind of mutation' or 'I'm only living here at the cost of many people.' And I've taken various viewpoints and thought many different things in order to comfort myself." After the rain, I could see a rainbow from the window. It formed a beautiful semicircle. I quickly climbed into my wheelchair to go outside.

"I envy someone who can ride in a wheelchair," said T-kun.

Hey, T-kun, I'll stick pins in your image!

I really wanted to say to him, "You're all right because you can walk." But I couldn't say it. The words might have ruined that beautiful rainbow.

Either Mom or Dad comes to collect me every Saturday. I stay at home overnight and then come back here on Sunday evening. I always have a fresh bruise somewhere on my body when I go home.

"Do you often fall over?" Mom asks me when she sees them.

"Well, because I'm so slow, I'm always pressed for time," I reply. "I ask the dormitory matron to wake me up at 4 a.m. and then I start studying. Otherwise I can't finish my daily duties . . . But the more I try to hurry, the stiffer my body gets, and I fall over."

With the motto "I must walk as much as I can!", I try not to use the wheelchair apart from when I go outside. But when I'm in a hurry or when I want to go to the library-which is located rather a long way away-=I use it to save time.

I'll accept commuting to school in the wheelchair! (To be honest, when I ride in it, I tend to think, 'I'm done for. I can't walk any more.' And that makes me feel more miserable.)

I met the matron in the corridor.

"Good morning," I said.

"Oh, Aya," she replied, "are you going in your wheelchair? It's comfy, isn't it?"

It was so frustrating to hear her say that. I had a chocking feeling and could hardly breathe.

What do you mean, 'comfy?' Do you think I like to ride in a wheelchair? No! What I want to do is walk. I'm very distressed that I can't walk. I suffer a lot from that fact! Do you think I ride in a wheelchair because I want to have an easy time?

I felt like pulling out my hair.

Mom's gray hairs are getting more conspicuous. Perhaps it's because my condition has taken a step backward.

Chapter 3 - The Start of Distress V

Understanding The Disabled

Today we held a small Sports Day at school. The warm May sunshine felt so good. It was also Mother's Day and my younger sister's birthday. So it was a day for congratulations.

I rang Emi, my cousin who lives in Okazaki, to ask her to visit me. I wanted her to know how desperately I'm trying to live . . . Emi and I have been close since our childhood. We used to stay at each other's house during the summer or winter holidays and share the same futon. She looked so nice that nobody would have thought she was still a third grader at high school. She has big eyes with long eyelashes and she'd decorated her twisted hair with a gold hairpin. She was wearing a while blouse, a flared skirt, and red slip-on sandals with high heels. She came with Kaori, her younger sister, who is rather boyish and, in fact, is often mistaken for a boy.

There's a secret patch over clover in the corner of the playground. The three of us planted ourselves down and started to look for a four-leafed clover. I wanted to fine one as a present for Mom.

"I wonder if we can really find one?" Said Emi.

I replied what had been in my mind for some time. "A four-leafed clover is just a deformed version of a normal three-leafed one, right? Why should something deformed be lucky?"

Emi thought about this a little, and then said, "Because it's unique."

Perhaps she's right. It's not so easy to find happiness. I suppose that's why we feel happy and say "Good thing we tried to find one!" when someone eventually does.

I fell over this morning and hurt myself. It made me cry. I have to become much stronger. I don't know whether it was because I was in a hurry or just rushing. When I tried to move my legs forward, they wouldn't move, and so my body tumbled forward. I caught the handrail, but it didn't support me enough. Down I went with a thud.

When I was being carried on a stretcher along the corridor to the nurse's room, I caught a glimpse of the blue sky.

"Oh," I thought, "it's such a long time since I saw the blue sky lying on my back!"

And when I was lying on the bed in the nurse's room, I could see the sky through the windows again. The white clouds looked very beautiful as they drifted across the blue sky. Right, in the future, whenever I'm stuck, I'll look at the sky. In the Sukiyaki song, Kyu Sakamoto sang, "I look up as I walk along, so my tears won't fall . . ."

That's good, that's the spirit.

I slept well for about an hour. I felt much better, so I got up and went to the toilet (the Western-style one). In the toilet, it struck me that perhaps Auguste Rodin came up with the idea of creating The Thinker when he was sitting in a toilet.

I'm always defeated by the fact I move so slowly.

Yesterday, it was my turn to do library duty. I eventually got there after taking about 20 minutes using the corridor on the second floor. But there was nobody there. I was too late. Half crying, I borrowed Wild Animals I Have Known by Ernest Thompson Seton. I cried, even though I knew I could contact the dormitory using the interphone if I was shut in the library.

Today I got there at about 4 o'clock. The student on duty sent me away saying, "Please leave quickly! If you wanted to look for a book, you should have come earlier."

Resentment! I felt pitiful. I'm twice as slow as the others, so I don't have time to spare. It takes too much time to do ordinary things (e.g. washing). It's not a matter of lacking good ideas and intentions.

Today we went on an excursion to the zoo. I don't like zoos anymore.

-The sad face of an orangutan. (I've heard that orangutans are nervous animals that easily get neurotic.)

-A chimpanzee throwing stones.

-A pelican who can't even catch a fish

-A battered ostrich.

Looking at all those creatures I got tired and depressed.

I hate the duty roster system at the dormitory. But I suppose it can't be helped because without it group life couldn't operate . . . Because I'm slow, I'm always one or two steps behind everyone else for any activities we do together.

In order to cover up my slowness, I finished cleaning half the room before I went for the radio gymnastic exercises in the morning. But when I got back, the room leader suddenly said, "Aya, you can't clean the room, can you? So take care of the towels and disposal boxes in the toilet!" I was frustrated that I didn't argue back when she jumped to the conclusion that I couldn't do it.

'Forgive everything, bear the unbearable, endure the unendurable . . .' In some ways, the teachings of God distress me. It's that way of thinking that has made me weak.

If I could move my body faster, I'd have been happy to go and clean the toilet. But I couldn't clearly express my opinion. I left the room without saying anything (although I was thinking, "You rat!").

As soon as I went out, I felt bitter and I started crying., The matron was just passing and said, "Aya, you know you shouldn't cry while living in a community like this."

What can I do?

I went home. I cleaned the parakeet cage. When I was walking, I felt a slight pain in the inner side of my left hip joint. I sighed, thinking that now my important left leg is breaking down . . . I was horrified to see the unnatural movement of my left hand (the five fingers move individually when I open my hand or bend them). I also have a pain on the left side of my chest, in the joints of my arms, and in my right buttock. Perhaps I hit myself in the wrong place when I fell over. I should put a poultice on again.

My right leg and knee sting. Finally . . . In the bath, I stroke them, murmuring, "I banged my lower back and shoulders when I fell over. Poor body, damaged all over!"

From today, I'll try to walk for 10 minutes every day. Here I am challenging my self to see how far I can walk! At this rate, I won;t be able to maintain a human elevation of 1.2 meters (the height of my eyes when I'm standing) when I'm in the third grade of high school.

I asked one of the students to show me photos of the third grade school excursion. I wonder if I'll be able to join the excursion next year?

In order to understand that I'm a disabled person:

1. Giving up. I must know my limitations and admit that I have a physical handicap. I'll make an effort from that starting point

2. Forgetting my healthy past self. I can run in my dream. According to Sigmund Freud's The Interpretation of Dreams, I have an incredibly strong desire (that's only a matter of course).

Tomorrow's the day for our student dance performance. I'm still lacking full awareness of being disabled, so I've been trying to dance beautifully. Actually, I think that spirit is wrong. I've practiced hard, but it hasn't gone very well.

As I was coming back today, feeling wrecked, the wheelchair motor at a low speed began to sound as if it was suffering as well.

"Am I so heavy? I'm sorry. Keep at it!"

I felt responsible for my weight of 35 kilograms.

Am I in high spirits today? No way. I'm just doing my duties because it can't be helped. I went to take part in the radio gymnastic exercises, had a meal, did some washing, took out the rubbish, attended the roll call . . .

The matron said "It's busy in the morning, isn't it?"

I wished I could have answered calmly, "I'll be busy the whole life." But my face just froze.

I think it's only when people are walking that they can really think of themselves as being human. For example, a company presidents thinks about ways of making more money while walking back and forth in front of his desk. And maybe that's why lovers often talk about their future while walking along together?

Suzuki-sensei's eyes

Remind me of an elephant's eyes;

A guardian deity in India,

An elephant knows everything.

I love those gentle eyes.I was in a daydream in the classroom. All by myself . . . I remember being told off by my teacher for running along the corridor and rattling my desk when I was at elementary school! I remember a boy having his bottom spanked for jumping out into corridor through the classroom windows. I couldn't do a practical joke like that. I only watched with a smile on my face. I should have done things like that while I could.

Jumping out through the window . . . No one was there. It was quiet. There was a windows and there I was.

THUMP!

"What the hell are you doing? That's dangerous."

The nurse's room had to help me again. A-sensei referred me as "a girl with self-injurious behavior." It was painful, but I had the satisfaction of going out through the window even if I had to crawl.

I won't do it again.

I was hoping that the movements of my body would get a bit better as it got warmer. But in fact they're getting worse. I was hoping to enter the hospital during the summer holiday to benefit again from some new medicine, so I went to see.

Cold words . . . I can't enter the hospital during summer holiday because they won't have any new medicine . . . I felt that I even medical science had given up on me! It was like being pushed off a cliff. Now I'm filled with a sense of despair. It's as though I've been hit on the back of the head with a hammer . . .

Chapter 4 17 Years Old (1979-80) - "I can't even sing anymore . . ."

For my birthday, Mom and Dad gave me five lovely notebooks and letter sets. Ako gave me a sand-glass. Hiroki gave me a blod-tipped ballpoint pen with four colors. He said I shouldn't cry any more that I'm 17. Kentaro gave me a book titled Shiroi hito, Kiiroi hito(White People, Yellow People) written by Shusaku Endo.

My Wishes on Becoming 17 Years OldI want to go to a bookstore and a record shot. It's difficult even in my wheelchair. I can't move my hands the way I want to, and I often make mistakes operating it.

If I could go to a bookstore, I'd buy Gone with the Wind and Anya Koro (A Dark Knight's Passing) by Naoya Shiga.

If I could go to a record shop, I'd buy an LP of Paul Mauriat's music.

I tumbled in the bathroom. I couldn't stay balanced on tiptoe (I may no longer be able to do that) and I fell down on my bottom with a thud. I wasn't hurt but I was scared. Yes, I'm scared.

I wonder if my disease can heal naturally? I'm now 17. I wonder how many more years I'll have to fight against it until God forgives me . . . I can't imagine myself at the same age as Mom is now (42). I couldn't imagine becoming a second grader at Higashi High, and now I'm afraid I may not be able to live till I'm 42. But I want to still be alive at that age!

Chapter 4 - "I can't even sing anymore . . ." II

Homecoming

I felt so happy thinking about going home for my first summer holiday from this school that I couldn't get to sleep. I'm sorry I can't enter the hospital again because they can't get any new medicine. But I think my new medicine in the future will be in tablet form rather than injections. I was told that they're making an effort to produce it, so all I can do is give up and wait.Just before lunchtime, an old man came to the house.

"I'm from Heiankaku Wedding Hall," he said. "Can I talk to your mother?"

"My mother and father are both out," replied my brother.

Five minutes later, we had a second visitor, a small middle-aged woman.

"I'm from Heiankaku . . ."

"Oh, your colleague came a few times ago," I shouted from upstairs.

"Is that your grandmother?" asked the woman.

My brother, who was at the door, burst out laughing.

"She spoke very slowly," the woman said, "so I assumed she was . . ."

Give me a break! Am I a 17 year-old grandmother . . .?

At dinner, my sister told mom about this episode. I felt so miserable. It annoys me so much to be told I have a disability. It's clear I haven't really admitted yet that I'm disabled.

I helped Mom prepare dinner.

She said to me, "Could you mix the Chinese chives and meat to make some gyoza dumplings?"

Ugh! Making gyoza dumplings? Involuntarily, I made a face. (I hate gyoza.) Still, it was all right, because the main course was chirashi zushi (a kind of sushi with the ingredients chopped and scattered over a bed of vinegared rice) . . .

As I was breaking four eggs and putting them in the pan to make some scrambled eggs, I suddenly thought about I-sensei. When she wanted to cook some rice in the morning, she would wake up and switch on the rice cooker instead of using the timer. I admired her because she didn't rely on machines. When we were making breakfast at school camp, she noticed I was coughing (I'd choked on some tea). She came over and stroked my back. She was a very gentle teacher . . .

When I was cooling the rice for the sushi using an electric fan, I put the pot between my legs and got burn marks about two centimetres long inside both thighs. I thought they looked rather beautiful-a slightly reddish color.

The members of Tanpopo no Kai (the group of handicapped people) work during the day and then get together in the evening to produce a mimeographed copy of their magazine called Chikasui (Underground Water). When I rang the group and told them I was staying at home for summer holiday, they invited me to join them.

"Mom is it only bad girls who go out in the evening?"

"Well, I suppose it's all right as long as you're with good people," she replied. "But isn't it a bit dangerous to go out in the dark?"

At 8 p.pm., Yamaguchi-san arrived in a car to pick me up.

Before I went out, I said to Dad "I'll be back soon."

He was lying on the sofa in the Japanese room watching television. He had had a drink with his dinner and his face was rather red. "Aya," he replied, "I'm rather worried about you going out in the evening. In the future I think you should only go out in the daytime."

I was so pleased to hear him say that. Actually it was a bit of surprise to hear advice from Dad. He doesn't usually interfere with his children. He puts on airs, but he's really a shy person. I prefer him when he's a bit drunk to he's sober.

Chapter 4 - "I can't even sing any more . . ." III

Falling Over

In the past, when I wanted to hurry, I could. Now, even if I want to hurry, I can't. I'm afraid that in the future I may even lost all sense of hurry. Oh God, why did you give me this burden? No, I suppose everyone has some kind of burden. But why is it only me that has to be miserable?

The way I fell over today was really pathetic. When I take a bath, either Mom or Ako helps me take off my clothes in the changing room outside the bathroom. They run some hot water on the floor of the bathroom to warm it for me. Then I crawl across the tiles to get to the bathtub. Today, when I was trying to grab the edge of the bathtub so that I could get into a half-sitting posture, I fell on my bottom. I was unlucky because there was a plastic soap dish right under me. It broke into pieces and fragments got stuck in my buttocks. I cried out in a loud voice.

"What happened?" Cried Mom as she flew into the bathroom.

She was very surprised to see a red river of blood mixed with the hot water. She placed a towel firmly on my bottom and then poured a lot of hot water over the parts of me that were still dry. Then Mom and Ako held me. They quickly dried off my body and got me into my pajamas. Then Mom covered all the cuts on my buttocks with gauze patches.

"With cuts like that," she said, "I think we'd better go to the hospital."

It turned out to be a serious matter. I had to have two stitches at the hospital and didn't get back home till around 9 o'clock. I was so tired.

It was a sudden accident, but I realize what was happening at the time. There was no real reason for me to stumble and fall over, or for my hands to slip. I wonder why a nerve can stop functioning momentarily? I felt sorry toward Mom for what I'd done.

While Mom was busy sorting out my many types of medicine to divide them into doses, I just lay in bed. I had a slight stomachache.

But whatever your excuse was, Aya, your attitude was wrong.

Partly because I was tortured by many conscience, I felt like readingOkasan 2 (Mother 2), a collection of poems by Hachiro Sato. My hand reached out toward the bookshelf.

Chapter 4 - "I can't even sing anymore . . ." IV

Asking My Self Some Questions

The summer holiday will soon be over. The only thing I've completed successfully during the holiday was looking after the parakeets. They come out on to my hands or shoulders and wait while their cage is cleaned. I give them some new water and feed, Then I put them back through the small door into the cage one by one. They;re so cute, They sometimes peck me, but it's not painful. I'm sure they're saying "Thank you"and I say, "You're welcome. I'm happy as long as you are happy." The whole thing takes about an hour as I talk to them. I get sweaty doing it, because I have to close all the windows so that they can't fly away . . .

Self-Reflection (Q&A)

"Aya, why don't you study much?"-"I don't know"

"Don't you feel sorry for your parents who work so hard?"

-"Yes, I do. But I can't study"

"You're spoiled, yo know! Look at the outside world. There are many people out there who are trying very hard on their own. In fact, one year ago, you were . . ."

-"Don't say any more! After Motoko-sensei told me that life is not all study, I began getting lost."

So, after all, I have to face the end of the summer holiday without having done anything much at all. I'm scared about starting the new term!

I'm the one who's most aware of the changes (for the worse) in my condition. However, I don;t know if they;re getting only temporary or they mean I'm gradually getting worse.

I explained the changes to Dr. Yamamoto:

- The movement of my hip joints is bad. They still move back and forth to a certain extent, but they will hardly open to the left or right. (I can't move my legs like a crab). And because my Achilles tendon is hard, it interferes with my efforts to move my legs forward.

- It's getting difficult for me to pronounce the ba and ma columns of the kana syllabary.

I wanted to ask th truth about my disease, but of course I'm scared to know. I don't have to know that. It'll be all right as long as I can live know as well as I can.

"Aya," said Mom in a spirited way as we were going home in the car, "you changed to Okayo because you couldn't continue your life at Higashi High School. You're quite a serious case even there. You may be feeling you're not accepted at Okayo, either, and gradually start shrinking with fear. But don't worry. You received the gift of life. And you'll always have a place to live. If you have to spend your life at home, we'll refurbish your room for you so that it's nice and warm and bright with lots of sunshine."

I think Mom wanted to cheer me up because I was looking so miserable.

"It's not like that, Mom, I'm only thinking about how I should live today. I'm not looking for an easy place to live."

That's what I was shouting in my heart.

I went to the washroom to wash my crying face and looked at myself in the mirror.

"What a lifeless face I have!"

I remember saying to my sister in a cool kind of way that I could find some charm in my face even though it was ugly. But I couldn't say that with the face I have now.The few facial expressions I have left include crying, grinning, a serious look, and a sulky face. I can't keep up a vivid and bright expression even for an hour.

I can't even sing any more. The muscles around my mouth have a kind of tic. And because of the decrease in the strength of my abdominal muscles, I can only whisper like a mosquito.

I've been talking the white tables every day for one week now. My talking tempo has speeded up a bit and it's become easier to swallow food. The tension in my right leg has been eased slightly. However, I still have difficulty moving my legs forward and they're still painful.

Chapter 4 - "I can't even sing anymore . . ." V

Autumnal Events

The School Festival

Mom and my sisters came. Mom said she was in tears watching I-sensei dance on the stage."How come?" I asked.

"Maybe it was because she looked like she was trying so hard. At an ordinary high school, only the students perform, don't they? I was moved by a teacher performing earnestly together with the students. I think that's why my tears welled up. And there was also that boy who played monkey and walked around like someone suffering from cerebral palsy. But in fact he can't help but walk like that. Maybe because it was a perfect role for him ,everyone laughed. That made me cry even more."

It struck me then that I inherited my crybaby side from Mom.

"But Mom," I replied, "around April, when I saw S-chan falling over and laughing, I thought she was superhuman. I wondered if I could ever become that strong. But these days even I can laugh when I fall over. I think everyone laughed when they saw that boy's monkey costume rather than that at the way he walked.

The Undokai Athletic Meet

I never imagined a school for the handicapped would have an athletic meet. I was wondering how the students could possibly all parade around if they couldn't walk . . . (I totally forgot that some people can walk, and there are also wheelchairs.) There was a real sense of fulfillment in completing something by helping and cooperating with each other and by contributing things that were lacking.The students in serious condition produced a creative dance performance themselves. When it was time for the autumn leaves to fall, stupid me got the wrong group and dropped them! However, I was dancing as hard as I could, just like a butterfly (at least in my heart . . .)

Because we were all serious cases, I thought it would be impossible to present a beautiful performance. But I was surprised when I watched the video in the library. What a beautiful show we put on! We can do it if we try.

One strong impression that remains was glancing up and seeing the fresh blue of the sky while I was dancing.

I think the biggest difference between this and the athletic meet I had at Higashi High is that I have changed from being an outsider to being someone who's involved. And I've changed my mind: now I realize that if I try hard enough I can do some of the things I thought I could never possibly do because of my serious condition.

The teachers encouraged me. They said things like, "Aya, you can do it if you try! The performance will be great," and "The dance warmed up thanks to you dropping the leaves!"

Dr. Yamamoto said a similar thing: "Little Aya, I think something in your mind has started changing because you're now aware that you're someone who's involved."

Suzuki-sensei came back from his long-term study and training course. He told me what he had studied while staying with children who have severe physical handicaps.

"Some are 10 years old, but their mental age is still the same as a one-year-old baby, so they won't respond to anything. They'll put anything in their mouth, even a stone or a lump of mud . . . Looking at those children, I realized there must be some kind of guidance suitable for babies. The point is we have to make endless efforts and have good techniques to give the appropriate guidance to each individual. Everyone's trying hard-those with a severe physical handicap, the teachers who guide them, and you and me, Aya. So, let's keep at it, shall we?"

Listening to his words, I felt rather ashamed and ungrateful. Up to now, I thought that I wouldn't be in so much pain if my intelligence's proportion to the inconvenience of my body . . .

When I was an elementary school student, I wanted to become a doctor. When I was a junior high school student, I thought of going to a university with a welfare faculty. Then when I was a student at Higashi High, I started thinking it would be nice to go on to a literature faculty. But even though I have changed my mind a lot, I have consistently had the feeling that I want to do some kind of work that is useful to other people.

I don't have any specific goals right now, but I wonder if I could provide meals or something like that for children who can't move? I'd like to help them understand the warmth of people by holding their hands. I wonder if I can at least be some use to someone?

A long time ago, Atchan said to me, "It might have been better if I wasn't born." I was so amazed to hear that. It was a comforting surprise because it blew away all the disgusting things that were deposited at the bottom of my heart along with many sighs. I had thought the same thing many times. But knowing that a child who can't even move doesn't have the chance to think that, I couldn't help feeling really sorry.

I can no longer return to my past. My mind and body are exhausted like a piece of old cotton cloth. Please help me, teachers!

I was tired out from crying, but I managed to answer a calculation table for commercial bookkeeping. My answer matched perfectly! I'm so happy. But it took me well over 55 minutes-that's not so good.

Chapter 4 - "I can't even sing anymore . . ." VI

The Year End

I wrote my New Year's cards. I only knew a few of the postal codes-including 440 (for Toyohashi City) and two or three others. I came across various codes this year, partly because I got to know my teachers and friends at Tokayo. Japan is a huge country.

Everyone's busy doing the year-end cleaning, rice-cake making and shopping. What should I do?

"Aya, you're in good condition, aren't you?" Said Mom.

"Can you wipe the floor?"

"Sure"

Mom squeezed the wet rags for me and then placed them on the floor a certain distance apart.

I'm losing my excitement about the New Year. Why can't I feel refreshed and think about some New Year's resolutions? I cried out loud, feeling that I've gotten stuck somehow. My stock keeps falling.

A teacher at Higashi High once said, "What's important for solving a problem about modern Japanese is to grasp what the question is asking and follow it with an open mind. To become open-minded, you shouldn't have any preconceptions. For that purpose, you must read a lot of books. The more you read, the less you will have preconceptions."

Yes, I will read a lot of books and associate with the many characters in them. I've just realized that consideration for others and their feelings is also fostered through reading. From time to time, I stop talking when I decide I can't be understood however much I try. Too many times I've regretted that later, thinking that I should have done something different. That's why I keep getting depressed.

I decided to write my first calligraphy of the year. I took out a new thin writing brush and rubbed down an ink stick. It's difficult to do calligraphy without a model. Life without a mode is even more difficult.

After practicing for a while, I wrote a good copy: the character sunao(meek).

Chapter 4 - "I Can't Even Sing Anymore . . ." VII

A Speech Disorder

I'm having difficulty pronouncing the ma, wa and ba columns of the kanasyllabary, and also the syllable n. During the chemistry class, I was called on to reply. I knew the answer was mainasu (minus) but I couldn't pronounce it. My mouth can form the correct shape, but I can't utter a sound. Only air comes out. That's why I can't make my self understood.

These days, I often talk to myself. Up to now, I didn't like doing that because I thought it made me sound stupid, but I think I'll try more now. It's good for practice for my mouth. Whether there's anyone else there or not, I'm speaking . . .

I thought of running as a candidate for the position of Secretary of the Student Council. I entered the same race when I was in the fifth grade at elementary school. There'll be a public debate between the candidates, so I must do some speech training. Ah, there are so many things to do, including training and studying. I'm up to my neck in it. Good grief!

I remember having a big fight with one of my classmates during those elementary school days. One day, I went for a walk to the square with my dog Kuma. My classmate was there with her elder brother and their dog. The fight started because she set her dog on Kuma.

"Why did you do that?" I asked her.

"Because my brother told me to do it," she replied.

I got really mad and said, "So would you commit murder without a second thought if your brother told you to do it? He isn't always right, is he?" (It's the kind of logic I learned from Mom.)

But she wouldn't stop her dog. Then a big fight between us humans broke out. It was so fierce! It was so intense! I didn't stop even when my head was pushed into a ditch. My younger brother and sister backed me up.

Yes, with such power and such a sense of justice, Aya should definitely run for a position on the Student Council.

My speech disorder is becoming more conspicuous. When it comes to conversation, both parties now need lots of time and patience. I can't say, "Er, excuse me . . ." while trying to pass someone. I can't have a proper conversation unless both the person I'm trying to talk to and I prepare ourselves for listening and talking. I can't even express moments of pleasure by saying things like "The sky is beautiful. The clouds look like ice cream."

I get very frustrated.

I get annoyed.

I feel miserable.

I feel sad.

And, in the end, tears fall from my eyes.

Chapter 4 - "I Can't Even Sing Anymore . . ." VIII

Frustration

One of the teachers stopped me today and said, "Aya, are you feeling frustrated?"

I went speechless. I suppose they must have concluded that from my questions, my essays, my drawings, etc. But damn it! How could they dismiss what's inside my heart simply as frustration?

From having a healthy body, I've turned into a disabled person and my life has greatly changed because of that. What's more, my disease is still advancing. Now I'm fighting against my self. I can't have any sense of satisfaction while I'm fighting. As I go through all this worrying I know everything won't be solved by asking someone to listen to me, but I just want them to try and understand how I feel, and support me, even if only a little. That's why I consult Suzuki-sensei, showing him my notebook that includes all my thoughts and worries. other teachers tell me that I should try to digest them inside my self. But I can't stand or even move because the load on my shoulders is too heavy.

"Do I look like a girl representing Frustration Incarnate?" I asked Mom.

"Everyone suffers from frustration," she answered. "It's better to be brave and say whatever you think on the spot. If you worry too much later about what was said to you, or the things that you did, they'll think you're always concerned about something/"

I know I don't respond quickly. I sometimes don't even admit to my self that I'm disabled. I'm in the depths of despair. But, strangely, I don't feel like dying, because I feel a time of fun will come some day in the future . . .

Jesus Christ said that living in this world is a divine test. Did he mean that while you're leaving you should be looking at yourself after death . . . ? I must read the Bible.

Chapter 4 - "I Can't Even Sing Anymore . . ." IX

Meals

I can no longer use chopsticks very well. My right thumb doesn't stretch enough and the other fingers get stiff and won't move, so I can't hold things between my chopsticks. The way I eat now has evolved naturally. I've mastered my own way of eating.

The menu for this evening included rice, fried prawns, macaroni salad and soup. first of all, I threw the macaroni salad on to the rice. I do that with all the fine, small stuff. I can manage to hold a fried prawn because it's big, but I'm not particularly good with noodles (although I love udon).

I have to be careful about swallowing. I often choke, so i have to transport the food with good timing, move my mouht in a certain rhythm, hold my breath, and then swallow.

Chika, my classmate, can't use her left hand well, so she brings her mouth close to the container to eat. Teru-chan puts everything, such as the rice, the side dishes, and the ingredients of the miso soup on to her plate to eat them. I'm somewhere in between them. I can use my left hand, so I can hold a bowl. That means I can pretend to look like an ordinary person.

A long time ago, I read a book written by Kenji Suzuki, the TV announcer. In it he said that when two handicapped persons meet an 'arranged marriage' meeting, the first thing they should do is reveal their weaknesses. Is my way of eating a weakness?

"Am I conspicuous because I'm so slow?" I asked the head matron.

"Rather than saying that," she answered, "I feel sorry for you."

It was a rather shocking remark.

I feel sorry that again at Okayo I have to have other people doing everything for me. Handicapped people are classified into two categories: serious cases and light cases. I'm classified as a serious case.

Chapter 4 - "I Can't Even Sing Anymore . . ." X

March

Congratulations to Ako and Hiroki for graduating from junior high school. Now you have to face the high school entrance exams. Good luck!

Feeling like going out into the fields

To pick the fertile horsetail shoots.

The spring rain silently drizzles down.

This spring brings only loneliness.

I'm really concerned about my future. I've already turned my back on my life without being aware of it. What's happened to my hopes for the future? I can no longer think seriously about what I want to be in the future. Let it be. The waves of my fate have washed me away. I don't even know what kind of occupations left for me.

"There'll be another year," says Mom.

"I only have one year," I think.

I don't knowhow to bridge this gap in our way of thinking anymore.

The students who come to school every day from Aoi Tori Gakuen Medical Welfare Center - and those who have been living in the dormitory since they were young - are different to me. They don't have any hesitations and they seem to live their lives very smoothly.

"We don't mind a cheat, but at least be punctual!"

Because I'm always slow and late, R-sensei and the head matron tell me the same thing. But take the cleaning, for example: I'm slow, but I still want to do the cleaning properly. I can't cheat like that . . .

Matron I is very kind. She envelops me in a mother-like love. I like her very much because she makes me feel relaxed. She says she can't sleep well at night, so I think I'll give her a stuffed animal. Matron Y is the one who always hurries me along, repeating that I'm slow. But she watched me quietly the other day for about 10 minutes when I was crossing the 3-meter-wide corridor at the dormitory. Their kindness differs in quality.

I overheard mom talking to one of the matrons:

"I'll Aya with me when I die."

I didn't know she was thinking that deeply. I realized that was a mother's love.

I forgot to push button to start charging the Machine (my electric wheelchair), so it ceased to be a machine. I was in trouble. I pushed it up the slope with all my energy. I had a pain around my lower back. I took a brief break on the connecting corridor on the second floor. I could see something small moving on the hillside when I looked down at the ground. It was a puppy. It looked lonely.

Just then a teacher passed by. "Ah, dogs like nice scenery, too!"

It struck me then that the feelings you have toward something that doesn't speak vary depending on the person or your mood at that time.

What should I do after graduation? In the past two years, my disease has become much worse. mom says I should concentrate on getting thorough treatment by consulting Dr. Yamamoto. It's no longer a matter of whether I can motivate myself or not. It's not a time for expecting encouragement, either. I just have to carry on.

I put my feet under the kotatsu heated table and ate some snacks. Ako had left for me. "Keep it up, Aya!" she said to me.

Recently I've been feeling something strange. Sometimes my vision gets blurry and my brain starts to reel. The shape of my right foot has also changed. The joint of my big toe is protruding and the other toes are kind of flat. I feel disgusted thinking that this is my foot. Now I'm 149 centimeters tall and weigh 36 kilograms. I hope my foot won;t lose the strength to support my body.

Do you hear me, ugly foot?

"I'm getting worse and I can't walk any more," I said to matron G when she was helping me charge my wheel-chair. "There was a time when my disease was at a mild stage and I could walk. In that state, I could have taken care of the others at the dormitory. But I came here after I'd become quite helpless, and now other people have to help me. I really feel sorry about that . . ."

Toward the end, it was difficult to get the words out properly, but I managed not to cry.

Mom was crying.

"It was your fate that you got ill, and it was also our fate as parents to have a child like you. Aya, I'm sure you are having a hard time, but we're having an even harder time. So don't get sloppy about trivial things. You must live strongly!"

When I was going back to the dormitory to change my clothes and get ready for the PE lesson, some phlegm got stuck in my throat. I almost choked to death. I can't get any abdominal pressure and I don;t have much lung capacity, so I couldn't get rid of it. It was very painful. I definitely feel I'll die one day because of some trifling little thing like that.

Chapter 4 - "I Can't Even Sing Anymore . . ." XI

A Third Grade High School Student

Thinking that my boarding school life will soon be coming to an end, I poked my nose into the Executive Committee to excess this year. I also worked hard for the Christmas party, eager to entertain everyone. I was so busy. But I was satisfied with myself this year because I did various activities for the sake of other people.

"I won;t let little things defeat me," said Mom, "so, Aya, you, too, will have to hang on for a prolonged war."

I was ashamed of myself for only thinking of the present. Spring will soon be over, As I put my hand out of the car window to catch the flower petals fluttering around, I could feel Mom's deep love. That gave me some peace of mind.

I'm more scared when I get up in the morning than when I go to sleep on my own. It takes me about an hour to fold up my futon and put on my uniform, another half an hour to go to the toilet, and then 40 minutes to eat breakfast. When my body isn't moving smoothly, it takes even longer. I don't even have time to look up at someone's face and say, 'Good morning.' I tend to look down all the time. This morning, I fell over again and got a nasty bang on my chin. I checked to see if it was bleeding. It wasn't, so I felt relieved. But I know that in several days I'l start feeling some pain, with bruises on my shoulders and arms.

I lost my center of balance in the bathtub and sank down bubbling into the water. Strangely, I didn't feel I might die. However, I saw a transparent world. I guess Heaven is like that . . .

I put my hand on my chest.

I can feel my heart beating.

My heart is working.

I'm pleased. I'm still alive!

The gums above my right front teeth are swollen. The nerves have died agian.

I went with the disabled group on an overnight trip. Many volunteers came along to look after us. Like a three-year-old infant in the rebellious phase, I had to keep saying, "I can do this by myselfm so I'll do it!" That stung my conscience. Etsuyo eats her food lying down. A girl who was passying by looked at her with a funny expression on her face. I'm glad I can eat sitting up. I began to think that we disabled people are all the same really, although our disabilities take different forms.

Rika, my four-year-old sister, was with us. She said a cruel thing:

"You aren't beautiful, Aya, you know, because you wobble."

I spouted out my tea involuntarily when I heard that. Young children are cruel because they say things in a straightforward way without considering whether someone may be hurt by what they say.

Chapter 4 - "I Can't Even Sing Anymore . . ." XII

The School Excursion

I was thinking it would be very difficult for me to go on the school excursion. But it seems I can go after all. Mom will come with me and Dad will look after the house.

A Record of My Impressions

Pigeons and me: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park

Pigeons and me: Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park

"Po-po-po" and "Kuru-kuru" the pigeons were cooing. At first they didn't come close to me (I think they were afraid of the wheelchair.) But when I held out some bird food, they came and perched on my shoulders, my arms, and my head. It struck me that both the pigeons and the people who dropped the bomb were very calculating types.

I went round the Peace Memorial Museum a few minutes ago. It was dark inside. Only the exhibits are brightly lit, so it's filled with a weird and heave kind of atmosphere. There's a model on display showing the time of the bombing. A mother and a child in tattered clothes were escaping from something holding hands. All around them was red with fire. It was the same color as the blood plasmawhich oozes out after I fall over and cute myself.

"It's revolting!" Mom muttered behind me. She turned her face aside and said, "I shouldn't say that, should I? I should say 'I feel sorry for them,' because they didn't want to be like that."

I didn't think it was revolting. That was not everything about the bombing. That was not everything about the war. A simple child like me, who doesn't know anything about war, was pretending to be tough like that.

On display were the cranes folded by Sadako, who died of A-bomb sickness. They were made using a kind of transparent red wax paper.

I don't want to die! I want to live!

I felt as if I could hear Sadako's cries. But, what kind of disease is A-bomb sickness? There are people who still suffer from it after 35 years, so is it hereditary disease? I asked Mom, but she didn't know exactly.

There was a stuffed horse with keloids, tiles burned by heat rays, 1.8 litresake bottles melted into limp shapes, some scorched black rice in an aluminum lunchbox, battered clothes people wore during the War, etc.

The reality of it all puts a merciless pressure on you. We didn't experience the War. But we can't turn away and pretend we don't know anything about it. Whether we like it or not, we have to admit that many people were killed by the bombing in Hiroshima, Japan. I think the best memorial for those who died is to vow that we will never let such a tragedy happen again.

After a while, I realized there were some elementary school children from Hiroshima inside the Museum. There were looking at the exhibits and me in my wheelchair with the same expression, as if they were looking at something horrible. I thought I shouldn't be concerned about other people's eyes.

"Perhaps a wheelchair and a wheelchair rider are unusual things to them."

Thinking like that, I could concentrate on the exhibits.

Suzuki-sensei callewd us and we went downstairs. I felt relieved to escape from the uncomfortable eyes and the heavy atmosphere.

Outside it had started drizzling. Mom tried to put a raincoat on me as I sat in my wheelchair. I tried to stop her, saying, "That's not cool." But nobody was saying anything, so I reluctantly did what she said. She placed a towel on my head as well.

The fresh greenery in the park was nice. The trees were all wet from the rain. They were shining under the cloudy sky. The fresh yellow-green leaves of the camphor trees looked beautiful against their black trunks. I wanted to sketch them.

We went deeper into the green trees and came to the Peace Bell. The rounded roof supported by four pillars represents the Universe. The dying lotus leaves in the pond surrounding the bell also seem to have a history.

"Anyone who wants to ring the bell, come over here," said one of the teachers.

I glanced over. Terada-san and Kasuya-kun rang it.

DONG . . . DONG . . .

The sound faded away into the distance with a lingering resonance.

"I'm listening to the sound of this bell wishing for 'peace' so I should do whatever I can, even though I won't ring the bell."

Thinking like that I closed my eyes and prayed.

Because of the rain, the water in the Ohta River was the color of earth. After the bomb was dropped, it was filled with wounded people. They were crying, "It's so hot, so hot!" Imagining the scene in my head was scarier than looking at the exhibits in the museum.

The pigeons came and perched on my shoulders and arms one after another. Their feet were soft and warm. They flocked around me pecking at the feed I was holding. There were loads of them. They're feral pigeons, so they're not particularly beautiful. I found one with bad legs. It was walking even though it was disabled one. I obstinately tried to feed only the disabled one. But I couldn't do it very well. There are so many pigeons in the park, I suppose it's only seriously disabled and couldn't walk, like me, perhaps it couldn't live. It struck me that I should be grateful that I was born as a person and can therefore stay alive.

Am I wishing for 'peace' because I'm person who can only live in a 'peaceful' world? That's a rather shameful wish.

After a while, I also felt like giving a piece of bird food to the other pigeons, not just to the one with bad legs. As I looked at the pigeons with their tottering steps picking up the feed, I thought about the sense of 'welfare' that we have in our human world.

Chapter 5 18 Years Old (1980-81) - Having Understood The Truth

I had rather a big shock today. Here's the conversation I had with four-year-old Rika:

"Aya, I want to be wobbly like you.""But then you couldn't walk or run, and you'd find it boring," I replied, as cool as a cucumber. "We've had enough of this problem with me."

"All right,I don't want it, then," she said immediately.

This happened in the entrance hall. Mom was some-where in the house. I wonder what she thought when she overheard us?

Final High School Summer Holiday

I took a bath in the morning (to make my body more supple). Mom was busily moving around saying how hot it was. I felt sorry for her because I didn't feel hot at all, so I worked on math calculations until I was sweating.

After lunch, I got a toothache. I took advantage of being at home to cry.

"How old are you?" Said my brother. That's a favorite remark of his. He put some ice in a plastic bag for me. That cooled my cheek and I slept for two hours feeling comfortable.

When Mom came home, she applied some Shin Konjisui painkiller to my tooth. Then I played gomoku with my brother. He beat me, 8 games to 2. Ako comes home late because of her part-time work. At my request, we had cold tofu and sashimi for dinner.

In the evening, I fell down again. As I was standing up to switch off the bedroom light, I fell down . . . SLAP-BANG. I made a terrible noise and Mom came flying in.

"What happened? Aya, you have to use your brain and build on the things you've learned up to now. If you keep falling down like this, I won't even be able to go out to work with an easy mind."

As she was saying this, she attatched a long string to the chain hanging from the light. I must be more careful about what I do late at night.

I cleaned my room enthusiastically, thinking "Today's the day!" I was moving around on my knees, so the vacuum cleaner didn't suck up the dust very well. But I worked desperately at it. I felt so good afterwards.

Keiko came to visit me.

Like Aquatic plants

Floating on a pond,

Talking with my friend,

Just looking at each other,

About our innermost feelings.

My friend with her sparkling eyes

Tells me about her dreams.

Floating on a pond,

Talking with my friend,

Just looking at each other,

About our innermost feelings.

My friend with her sparkling eyes

Tells me about her dreams.

Keiko talked a long about her future dreams. I felt this was how we would become adults.

Tomorrow's the day for me to enter the hospital again.

Chapter 5 - Having Understood The Truth II

Second Hospital Stay

(Nagoya Health University Hospital)

This time, the main tasks will be checking the progress of my disease, having injections of a new medicine, and undergoing rehabilitation. The difference from the previous stay is that I've been asked not to go out alone (because of the danger of falling down).

When I went to the toilet, I glanced outside over the window-sill. I felt depressed when I saw the gray walls and black buildings.

"Why do you look so tired?" asked the nurse who was accompanying me.

My nystagmus (involuntary movement of the eyeballs to left and righ

t) is becoming more conspicuous these days. I had an eye check in the room for brain wave tests. The doctor there has a bad leg, too. It struck me that I could work if only I had at least one part of my body that functioned properly.

"Why are you putting that cream on?" I asked.

"Because you're having checkup," the doctor replied.

That answer struck me as a bit off the mark. I wonder if he responds like that to ordinary people? Perhaps I look stupid because I have both a physical handicap and a speech disorder.

Dr. Yamamoto took me to Nagoya University Hospital in her car to carry out further tests. If I suddenly look right gazing forward, the red ball I can see

gets blurred, divided into two parts. This time I tried looking left all of a sudden. The degree of blur was less on the left. As I thought, the disorder of my right motor nerves is progressing more. In the car, I told Dr. Yamamoto that after the injection I don't feel sick like I used to and I was wondering if that meant the new medicine was no longer working on me. I also told her that although my Achilles tendon seemed to have softened, my speech disorder was getting worse.

"As for the speech disorder," she sad, "the best thing is to finish saying what you want to right up to the end, even though you may find it difficult to pronounce all the words. Ideally, people will get accustomed the way you speak."

Chapter 5 - Having Understood The Truth III

Training

1. Using a pair of crutches. (I almost fell over because I haven't got much strenght in my right hand).

2. Practicing standing up from a chair.

3. Though I was told I wouldn't be able to walk unless I could kneel, I felt dizzy and couldn't do it well.

4. Handiwork: knitting, making things, etc.

The 20th day in hospital. I had the second round of tests on my functions.

"There are no big changes," they told me.

I was shocked!

"But you haven't gotten any worse," they added.

That's no good! I have to get better-even if only a little.

I went to the Rehabilitation Room. There were many physically handicapped adults in there, but not many children. There was a man who wasparalyzed on one side as a result of a stroke. As he watched me gritting my teeth as I tried to kneel on a mat, he was wiping his tears away. With my eyes, I told him, "Look, I really can't afford to cry now. I'm in so much pain, I want to cry, but I'll save that until I can walk. You should keep at it too, OK?"

I feel uneasy and anxious about how much effort I'll have to make in order to be able to walk. When I returned to my room, I held some knitting needles-though rather than saying 'held', it would be more accurate to say 'grabbed.' Once I've grabbed them, I can't let them go again; my body gets stiff and I can't open my hand or clench my fist. It takes me up to 30 minutes to knit just one row.

I think I'll practice the kindergarten song Musunde, hiraite (Clench your fists, open them . . .), keeping it secret from the other patients in my room.

Ehenever the hospital director or the doctor in charge comes round, a lot of young interns follow them. Their conversation makes me feel sad:

Item 1. The computer route inside my cerebellum is broken, so the movements which ordinary people can do involuntarily are only possible after the instructions have been fed back once to my cerebrum.

Item 2. My occasional grinning is pathological.

The interns listen seriously to the director or the doctor in charge, but I feel rather bitter. It's not nice to have yourself talked about like that. I like the interns because it's fun when we talk about books or friends, but they become different during those visits when they peer at me with curiousity. However, they can't become good doctors unless they study hard, so I guess it can't be helped . . .

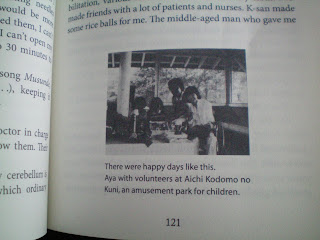

I can move busily around the hospital thanks to the splendid service of my wheelchair - when I go for rehabilitation, various tests, and treatment on my teeth. I've made friends with a lot of patients and nurses. K-san made some rice balls for me. The middle-aged man who gave me

a melon invites me in the evening to watch TV with him. One intern nurse brought me an ice cream. he middle-aged woman in Room 800 arranged some flowers in a vase for me. I read a nursery tale with Mami-chan. I feel like they're all my relatives. When one middle-aged man was leaving hospital, he said to me, with tears in his eyes, "Aya, do your best till the last minute!" I really have c chance to meet a great variety of people. Everyone says "You're a good girl, Aya. I admire you." (But I feel embarrased because I don't think I'm a 'good girl' at all.) I've only been here for a short period, but I'll never forget you all.

Chapter 5 - Having Understood The Truth IV

Graduation

As graduation day approaches, the topics in all the classes have focused on attitudes toward entering society with a handicap and possible places of employment. When I entered Higashi High, I studied with the goal of going on to a university. When I was a second grader at Okayo, I could still walk and thought I could find employment. But everything became impossible when I became a third grade student.

**-kun = ## Company

**-san = a vocational training school

Aya-Kito = staying at home . . .

That's the route fixed for me.

**-san = a vocational training school

Aya-Kito = staying at home . . .

That's the route fixed for me.

For the last two years, I've been taught to 'acknowledge being disabled and start from there.' I've had to suffer and fight a great deal. Every time some bright light came into my life, I had to experience a burst of heavy rain or a typhoon . . .followed by more fine days. I've reached graduation always carrying a feeling of instability. How much longer will I have to suffer and fight until I can find my life? I wonder if the disease gnawing away at my body will refuse to release me from agony until I die - as if it doesn't know the destination?

I wanted to be useful to society in some way, making the best use of the knowledge I've acquired from twelve years of school life and all the things I've learned from my teachers and friends. However small and weak my power might be, I'd have been so pleased to give something. I wanted to do something out of gratitude for all the kindness I've received from everyone. One thing I can dedicate to society is my body, for the sake of medical advance: I can ask for all my usable organs, such as kidneys and corneas, to be distributed to sick people . . .

Maybe that's all I can do?

Chapter 5 - Having Understood The Truth V

At HomeI had a feeling of nostalgia as I unpacked all the belongings I used during my boarding school life. Now I feel like an old woman. Mom and Dad go out to work and my brothers and sisters are spending their regular lives, commuting to school and nursery school. If I'm the only one in the family leading an undisciplined life, I'll become a burden to them, so I should at least try to lead a planned life:

1. I'll address people properly: "Thank you," "Good morning," etc.

2. I'll try to speak words sharply and clearly.

3. I'll try to become a considerate grown-up.

4. Training. I'll gain some strength and help with the housework.

5. I'll find something to live for. I don't want to die while I still have things I must do.

6. I'll try to stick to the family routine (times for meals, baths, etc.)

2. I'll try to speak words sharply and clearly.

3. I'll try to become a considerate grown-up.

4. Training. I'll gain some strength and help with the housework.

5. I'll find something to live for. I don't want to die while I still have things I must do.

6. I'll try to stick to the family routine (times for meals, baths, etc.)

Damn! Damn! I bang my head against pillow.